Talk at Walker Art Center About the History of Black Face

T wo years ago, Kara Walker came beyond a news story in an edition of the 19th-century Atlanta newspaper the Daily Constitution. The year was 1878; the piece described, in excruciating particular, the recent lynching of a black adult female. The mob had tugged downwardly the branch of a blackjack tree, tied the woman'south neck to it, and then released the branch, flinging her trunk high into the air.

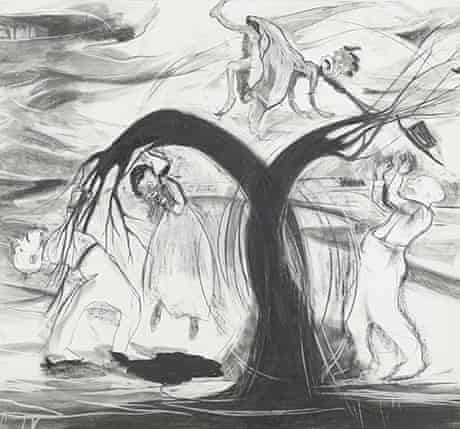

This terrible fragment of the past has made its way into a big graphite cartoon, now hanging inside the Camden Arts Centre, London, where Walker is about to have her first major UK solo evidence. Similar much of her piece of work, the cartoon is both cute and disturbing: here, in grotesque, cartoonish monochrome, is the blackjack tree, the lynched woman spilling blood, her assailants laughing every bit she dies. Equally I stand and stare, Walker tells me why she was and then fatigued to the story. "Information technology's this completely absurd, extreme, violent situation that required and then much perverse ingenuity."

Her London show is non big – simply three rooms, with 11 recent works – but information technology is significant and overdue. Walker is one of the about uncompromising gimmicky American artists, not just for the quality of her work – which comprises drawing, pic, and her signature medium, silhouettes – just for the fact that her art engages with what many would rather forget: the appalling violence meted out to the blackness population before and later the American civil war and the abolitionism of slavery, and the legacy of racism that still shapes the Us political agenda.

Another drawing, Urban Relocator, shows a hooded, Klan-like figure side by side to a blank cotton fiber tree: this is, Walker says, partly inspired by the boll weevil cotton plague that – along with the violence many freed slaves endured – led many blackness families, including Walker's, to carelessness their state in the s for a better life in the northern states. "My own family were once given a piece of land," she says. "I started thinking almost what happened to that land; virtually what made so many people get out the south, whether it was social violence, or domestic terrorism, or economic strife."

Walker is at her most provocative when interrogating the stereotyping that defined race relations in the antebellum south, and still exists today. The largest room in her evidence is lined with "wall samplers": the cut-out silhouettes that show figures engaged in tearing or exaggerated acts: a man bending downward to fellate an oversized phallus; a adult female in a wide-skirted wearing apparel property a severed head. The effect is to make united states of america question not only the cultural representations of black people (in that location is, every bit Walker points out, a whiff of "minstrels and blackface" about some of the figures) but also our assumptions about how skin colour defines anyone's physical characteristics and behaviour.

Walker has exhibited widely in the United states, and at 27 (she's now 43) became the youngest person ever to receive the prestigious MacArthur Foundation's "genius grant" scholarship. But she has also caused controversy. Exhibitions of her work often provoke strong feelings: staff at a library in Newark, New Jersey, recently reacted with outrage when ane of her drawings was displayed in that location, prompting the head librarian to cover it up. And dorsum when she received the MacArthur grant, she was lambasted by several older African-American artists, including Betye Saar and Howardena Pindell. "There were two strains of criticism," Walker says. "One was about the work, and who was looking at it, and me feeding into the viewing audition'due south preconceived ideas about black people. And the other was that I was just some highfalutin then-and-and then."

Her begetter, the artist Larry Walker, published a letter in her defence. It was under his tutelage that she had get-go decided to get an artist: she started drawing and painting when she was three. She says neither of her parents has ever felt completely comfortable with her work – her mother walked out of a screening of Fall Frum Grace, Miss Pipi'south Bluish Tale, a sexually explicit shadow-puppet picture show that features in the London evidence – but her father argued that his generation of black artists had fought to give future generations the right to brand art of any sort. "He was saying, basically, that I should be able to do whatever the hell I want. I retrieve that's what I'm ever battling confronting with my work – part of me wants to resist the pull to be doing what's expected of me as a black artist."

Information technology was while studying art as an undergraduate in Atlanta that Walker first felt this pull: an expectation, from her professors and swain students akin, that as a black artist she should be striving to represent the "black experience" positively. "I was making big paintings, with mythological themes. When I started painting black figures, the white professors were relieved, and the blackness students were like, 'She's on our side'. These are the kinds of problems that a white male creative person just doesn't take to deal with."

A fundamental moment came when Walker discovered Adrian Piper, the conceptual creative person and philosopher who, in the 1970s, fabricated a serial of performance works featuring herself as an androgynous, racially indeterminate immature homo. "It was the first vocalization that resonated with me, in talking about race with objectivity and sternness," she says. "Until then, I only knew 'black art' in the romantic sense – that it was only about positive representations of African American life."

Walker began to think nigh what she really wanted to say. She was built-in in Stockton, California, and moved to an Atlanta suburb at the age of 13, when her male parent took a task at that place. After liberal California, the racial tensions of the south came every bit a shock. "I just didn't get the rules," she says. "I didn't know what the story was that made people deport in very detail ways that I thought were prescripted and unnatural. I started looking for my own indicate of origin: maybe the point of origin was being American, or beingness black, or being a woman. I idea, 'I'll beginning with the foundation of this idea of a place, of America, and then piece of work my style frontwards.'"

Walker sees a direct line between the racist historical attitudes she examines in her work and current events. She took a road trip last yr with her daughter from Brooklyn, where she lives, to the southern states. They visited diners where the heads of old white men turned to give them "the xx-second stare". They swam in a motel pool, watching the other (white) bathers suddenly vanish; Walker heard a small girl say to her father: "I idea there were no niggers here."

So there is the rise of the Tea Party movement, and the distasteful obsession with Barack Obama's skin color. "In that location'southward so much suspicion effectually having a biracial president," she says, "around Obama's presence on the world stage – the fact that the Tea Party gets coverage every bit anything other than a fringe group. In that location's nada Obama can say or practise as a black man that they're [willing] to hear."

Walker is by now used to viewers beingness discomfited non only by the fact that her work dares to speak openly about race and identity, but that it may fifty-fifty be making fun of such viewers. "It makes people queasy," she says. "And I similar that queasy feeling."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/oct/10/kara-walker-art-shadows-of-slavery

0 Response to "Talk at Walker Art Center About the History of Black Face"

Post a Comment